What is a decentralised voting system and how can it build trust?

The problem of securing the voting process through centralised e-voting solutions

There is a clear rise of civil society’s mistrust in institutional central authorities, affecting the higher levels of governance, and calling for procedures to ensure the transparency and reliability of decision making processes. Elections are no exception, as more and more voices raise doubts as to the integrity and fairness of the traditional election process and the required auditing mechanisms. In 2018, the Election Audit Summit, led by Caltech and MIT launched with the following observation: “For nearly twenty years Americans have been faced with questions about the integrity of their country’s elections. Challenges to election integrity arise for a variety of reasons, ranging from bad luck, to mistakes, to malicious behavior. The possibility that something might happen in the conduct of an election that might place the correctness of its conclusions at risk have led many to ask the question: “How do we know that the election outcomes announced by election officials are correct?”*

The last US election is one of many examples where the integrity of the voting process was severely questioned, casting doubts as to the correctness of the announced results. Trump’s camp claimed that Republican observers were not allowed access to the polling stations to audit the process. Whether this was actually true or not does not change the fact that the lack of transparency and scalable fullproof verification makes for a great terrain for the seeds of distrust to be planted by actors trying to challenge the legitimacy of democratic processes. Such challenges put into question the impartiality, the efficiency and the resilience of centralized election authorities. This is true for any type of elections: from a nation choosing its next president to a DAO voting for the attribution of a grant to some of its contributors.

Electronic voting came into the picture in the last couple of decades offering a promising alternative to traditional paper voting. Not only does it offer to reduce the logistical complexity of elections and increase efficiency, it allegedly replaces the human factor, potentially corrupted and prone to error, with robust and verifiable computation. Computation thus offers a compelling alternative to human verification of eligible voters’ lists, of election timings, and of the casting and counting of ballots. At first glance, one could thus expect that automating the voting process would make for fairer trustworthy elections. However, e-voting systems operate in highly centralised non-transparent settings, with private voting companies now holding the integrity, privacy and fairness of elections into their hands.

Indeed, to process all this data in an automated, synchronised and secure way, companies operate information channels and servers with the necessary storage space and calculation capacities to implement the chosen voting protocols. This requires voters to take a significant leap of faith. Anonymity for instance is ensured through encryption, and the electronic ballots are kept and verified by computational methods, but the company offering this e-voting service acts as a trusted third party centralising and processing such data. It could very well accidentally modify, intentionally censor or add votes, leak private information, or be the target of the same legitimacy challenges the traditional electoral authorities are increasingly facing.Whether the service provider is reputable or not is not the issue. As long as participants cannot take part in the verification process, centralized authorities are, by nature, structurally fragile.

Distributing trust through designated committees and threshold cryptography

Often then, the problem of a centralised election authorities is dealt with the introduction of a designated set of relatively independent election authorities and distribution of trust amongst them. This is in turn justified by the following implicit assumptions:

- there exists a natural set of parties that have conflicting interests;

- each voter has in this set at least one party they can trust;

- the conflict of interests between these parties is sufficient to ensure that they will not collude.

In this paradigm, threshold cryptography can be useful as in order to decrypt an encrypted message, or to sign a message, several members (more than some threshold number) must cooperate, something which is in theory prevented by existing conflicts of interest. Formally, this is how an “honest” election authority is defined.

However, reducing “honesty” to the impossibility for authorities to coordinate and achieve dishonest purposes is in many ways problematic. Naturally, if someone had the intention to cheat you, you wouldn’t consider them honest just because they did not succeed. The moral value of a person or group of persons depends on their intentions and not on the sole outcome of their actions. But this isn’t problematic just from a moral stance, which one could deem irrelevant with respect to the formal issue of ensuring electronically secure, transparent and privacy-preserving elections. The notion of conflict of interest, in terms of which the formal property of “honesty” is defined, is far from obvious.

Not only is it difficult to assess the intentions and motivations of individuals, let alone institutions and other entities, but their conflict or alignment is further a “local” property and not a “holistic” one. This means that individuals do not have conflicting interests in absolute, but rather with respect to a particular goal. For example, in the context of voting, one naturally assumes that an election authority should not side with a particular candidate or proposal, and that individually supporting different election outcomes should guarantee that the election committee as a whole, will not be able to cooperate to push in one direction or another. But one could very well imagine that committee members, while having conflicting interests concerning the election outcome, all might have individual interests in breaching the privacy of voters, collecting, studying or directly selling voters’ private information.

Decentralisation: degrees and kinds in the context of onchain voting

This is where the blockchain paradigm for full decentralisation comes into play. Total decentralisation aims to eliminate any dissymmetry among the parties involved, i.e. the actions they can perform, the privileges, rights and obligations they have with respect to the voting protocol. Indeed, blockchain technologies open new horizons towards secure decentralised processes that will no longer rely on any trusted third party, either by direct human intervention or by controlling the information systems involved. In the context of voting, blockchain-based solutions have the potential to solve some of the trust issues by carrying out, in a decentralised way, the execution and auditing tasks currently performed by designated committees/authorities or centralised information systems. The community of voters could act as their own election authority: securing, executing, and auditing the election processes to which they partake. Blockchains provide a secure broadcast channel for the voters to communicate and transparently coordinate the election process.

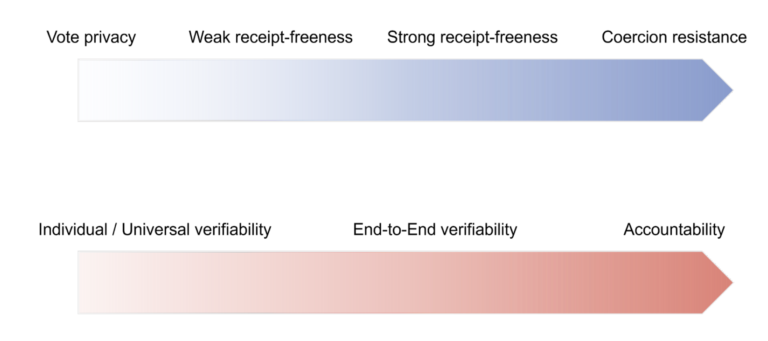

However it is important to stress that “Blockchain-based voting” paves the way for, but is not in itself synonymous with, total decentralisation. In fact, this term designates a family of voting solutions ranging from partial to total decentralisation. Like the term “electronic voting”, which refers to any voting process where automated computation intervenes at some point or other, “blockchain-based” is loosely used to refer to any voting solution executing some part of the voting process on-chain. More precisely voting systems are counting systems with two important types of properties: integrity-type properties and privacy-type properties. Intuitively, the integrity of an election refers to the ability of voters to detect fraud in the electoral process, while privacy refers to the fact that the ballots remain secret and are not traced back to the voter. Now, these intuitive requirements of integrity and privacy can be further specified and formally fleshed out in terms of stronger or weaker properties. A voting system may for instance allow each voter to check that their ballot was tallied as intended (“individual verifiability”), or might further allow any member of the public to verify that every recorded vote is correctly included in the tally (going all the way to “end-to-end verifiability”). In the same way, privacy might be taken in a weak sense as a guarantee that voter identity is never revealed, or in a stronger sense, meaning for instance that a voter cannot create a receipt which proves how she voted (“receipt freeness”).

Now, properties along these two dimensions involve different trust assumptions which can be lifted by making use of decentralised networks so that no election software, hardware, election officials, or even external observers need to be trusted to ensure that elections are run correctly.

Why not have it all? Them who can do more, can do less. Well… not exactly…

Up to now, there is no deployed system, nor any formally/theoretically defined protocol, to actually reconcile maximal integrity and privacy in a totally trustless manner**. And one might wonder: if decentralisation can achieve strong verifiability in a trustless setting, and can also ensure strong privacy with no trusted third party, why is there no system combining both?

The answer lies in the nature of the two types of requirements. In a decentralised setting, removing trust assumptions from the voting process requires a subtle trade off. There is indeed an intuitive tension between privacy and verifiability, especially in their strongest forms. While trustless systems can achieve strong verifiability along with weaker forms of privacy, there is no certainty that they can move up to stronger forms of privacy without having to lower the verifiability requirements, and vice versa. The observed tension can be put as follows: while verifiability involves some sort of tracking of votes, some level of transparency, privacy involves the impossibility to trace votes back to their voters. Whether full transparency and total traceability are compatible with strong privacy properties such as coercion resistance, thus remains an open question. Up to now, such tensions are not entirely understood and studied, and are in fact often implicitly brushed under the carpet by reinjecting centralisation into the system in the name of efficiency.

* Election Auditing. Key Issues and Perspectives, summary report of the Election Audit Summit, Caltech/MIT, December 2018

** Apart maybe for traditional paper based elections deployed on a small scale, and in particular with a single polling station with all voters collectively tallying the ballots.